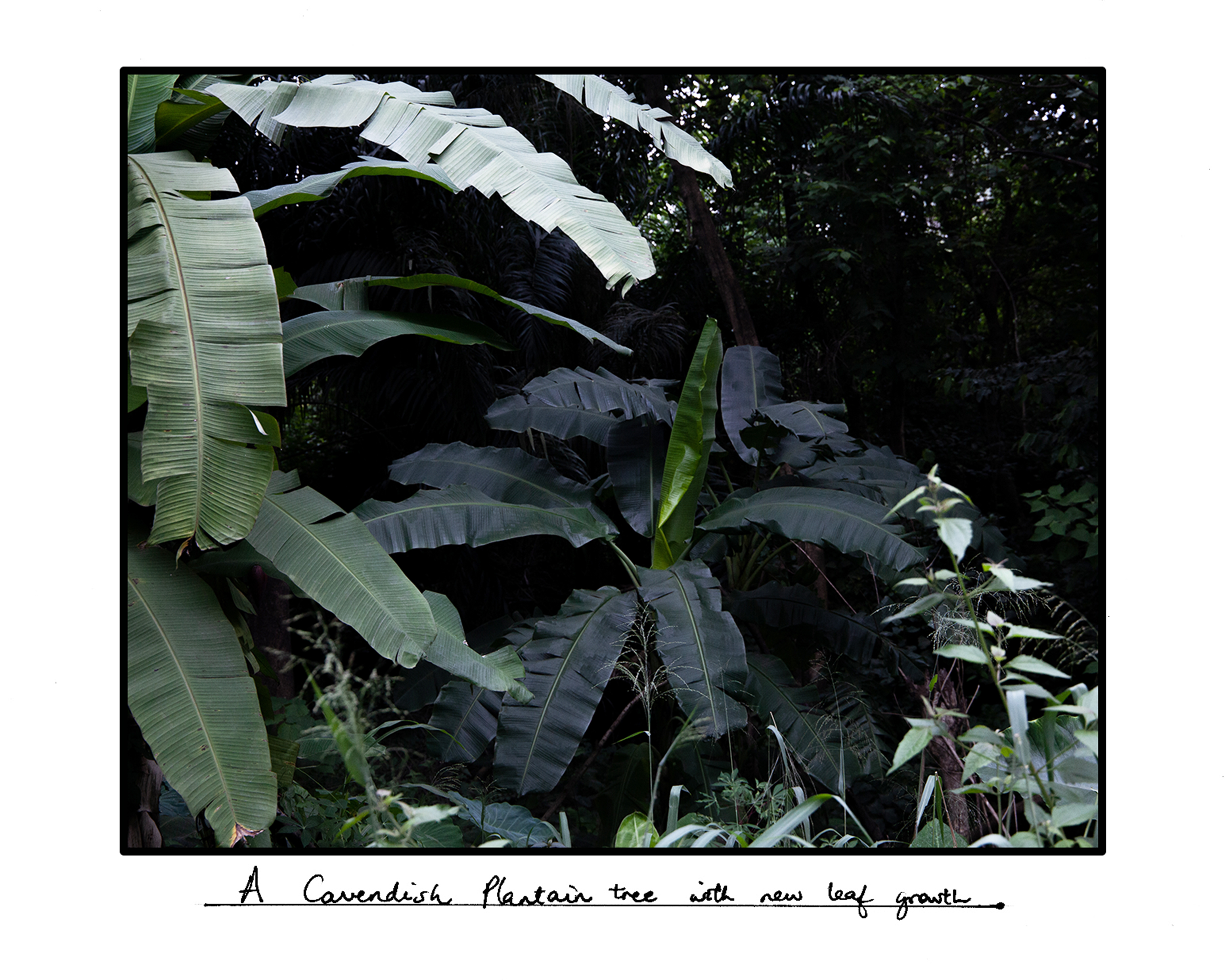

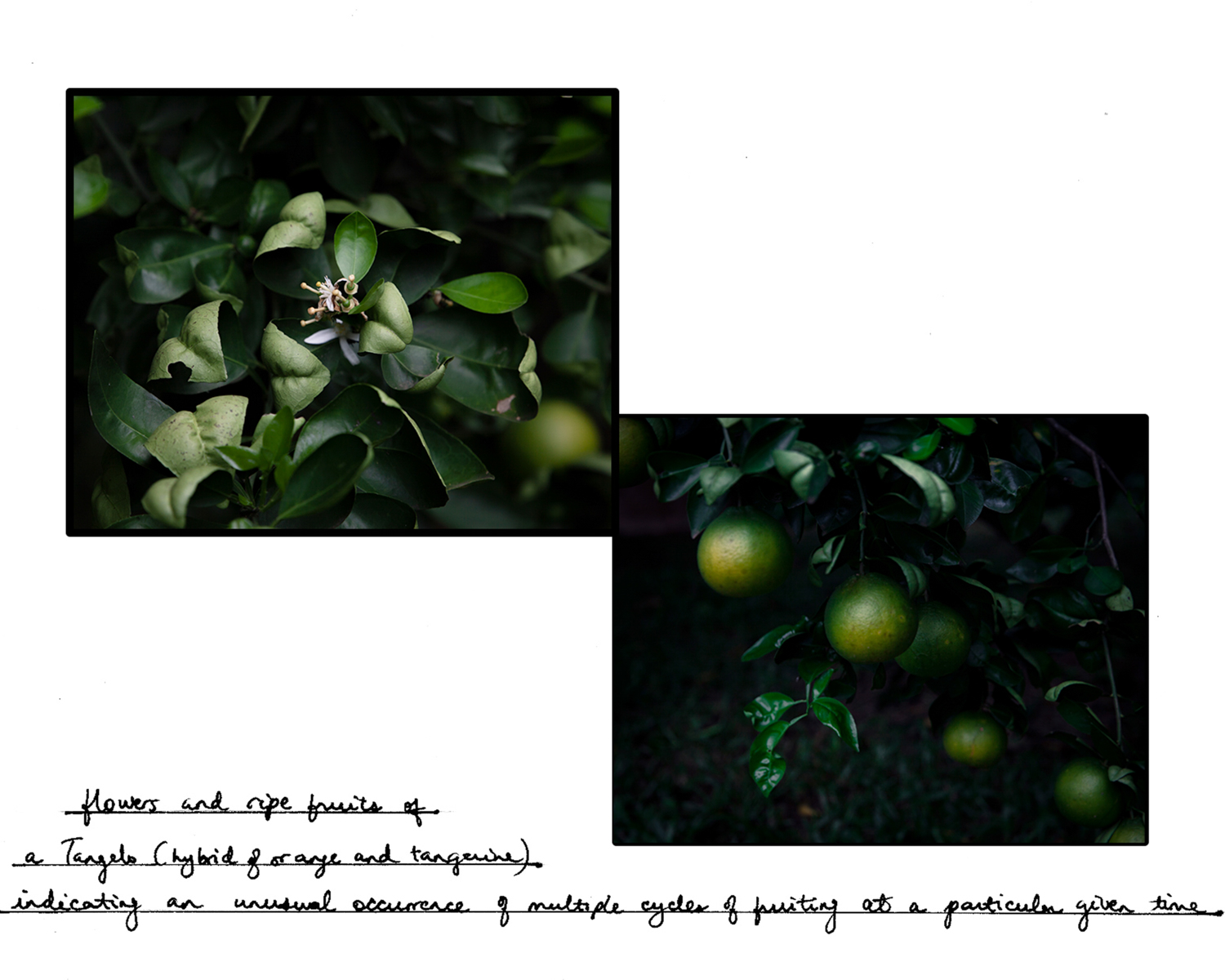

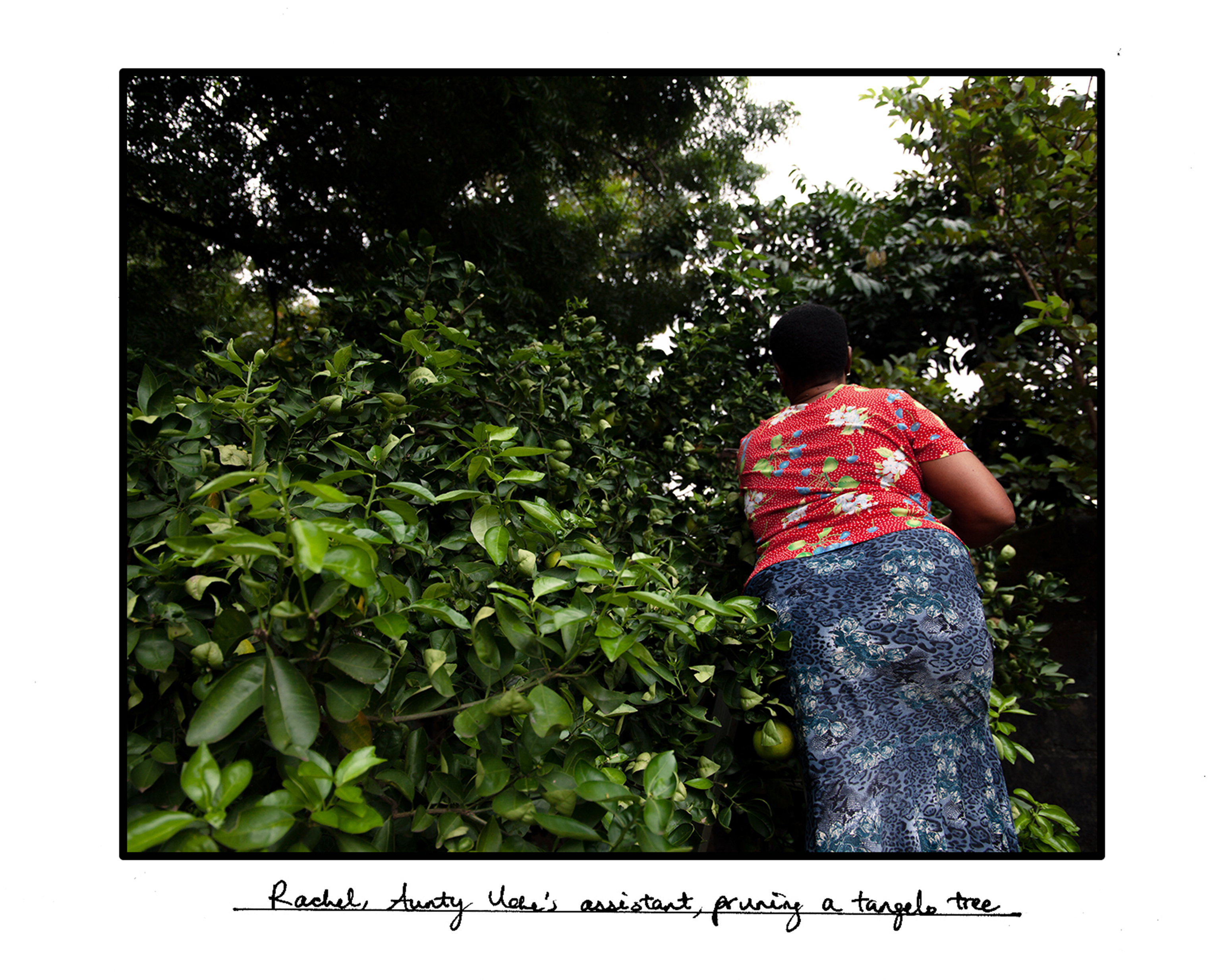

Aunty Uche’s Garden

It has been 15 years since Aunty Uche and her family moved into this compound with a vast expanse of land where she grows both flowers and crops. The land, big enough to be called an estate, has a fence separating the compound from a stream.

I got to know about her through Instagram: I was looking for florists in Enugu. Every week for months during the pandemic, I went there to learn more about plants, indulge in their beauty and let their grace wash over me. On the first day, my wandering destructive fingers crushed a bud and soon I learnt that the cost of such carelessness could be an entire paw-paw tree. I also learnt how lessons from the Parable of the Barren Fig Tree from the Bible (Luke 13:6-9) helped her save one of her paw-paw trees and plant gist like how you can tell species of mango trees apart by tasting their leaves.

The photos in this project were shot over the weeks since I met Aunty Uche and intentionally formatted as postcards dispatched from her home. I also sat down with her to talk about the home she has made out of the land.

Copyright: Immaculata Abba (2017 - 2024)

Web design: Immaculata Abba

Web design: Immaculata Abba